The Making of a Plastic Surgeon- Two Years in the Crucible Learning the Art and Science

Chapter 9- Chief Resident for the Veteran's Hospital and Jackson

“It is essential that we provide the best possible care for our wounded and disabled veteran’s.”

Tom Udall

For surgical residents, the status of chief year represents the culmination of the preceding years of training. We are now regarded as capable and competent to do most operations with minimal supervision or no supervision. We are expected to help train the surgeons junior to us. Once we are done with the chief’s term we are regarded as ready to go into practice for ourselves and seek board-certification. Our education, however, never ends. Surgery is one of those professions where you must continue to learn and hone your craft your entire career.

The end of my term working with Dr. Millard left me with ten months remaining to complete my residency. For two of those, I returned to the hand service. The two remaining four-month blocks were at the Veteran’s Administration (VA) Hospital and Chief Resident at Jackson Memorial.

The VA hospital was just across the street from the Jackson Memorial campus, but it was a world apart. Like the Wonderland of Alice’s adventure, the VA was an alternate universe. Jackson was affiliated with the University of Miami and was also the county hospital for Dade County, Florida. It was run by a public health trust. The VA was run by the Federal Government. The rules of engagement were totally different. Whereas some patients at Jackson were a source of revenue, at the VA all patient care was paid out of its share of the federal budget for the fiscal year. VA patients were heavy utilizers since they did not pay for care. The VA hospital had a fixed budget and, if funds ran out before the end of the fiscal year, services had to be curtailed. On the other hand, if the year ended with a surplus, the budget for the next year would be cut back. It was a classic Catch-22 that resulted in a perpetual, usually futile, struggle to hit the annual budget target perfectly.

The Chief of the Division of Plastic Surgery at the VA was Dr. John Devine. He reminded me of Mark Twain, with the same wild, white hair, bushy eyebrows, and mustache. A general surgeon, inventor, and talented sculptor he was profiled in Life Magazine in 1952, the year I was born. Devine sculpted hands and his models included jockey Eddie Arcaro, Yankees’ catcher Yogi Berra, and Louis Armstrong. In 1977, at the age of 64, he decided to become a plastic surgeon. At first, Dr. Millard refused him a residency slot, but did accept him for one of the three-month fellowship positions. Devine impressed him with his energy and drive and Dr. Millard subsequently offered to take him as a resident. Devine still holds the record as the oldest person ever accepted into a plastic surgery residency; he may well be the oldest accepted into any residency. He obtained his Medicare card before he became board-certified! Accepting him into the residency was entirely in character with Dr. Millard’s penchant for choosing residents with unusual backgrounds. Perhaps because their ages were close, they became fast friends. After completing his residency, Devine stayed on in Miami. Dr. Millard performed a facelift on him and off he went to practice briefly, doing a lot of hair restoration surgery, before eventually assuming the position of Chief of Plastic Surgery at the VA in Miami in 1985.

By the time I began my residency in 1987, Devine’s role at the VA was exclusively administrative. At 74, he no longer performed surgery or scrubbed in to assist. The plastic surgery resident assigned to the VA was, therefore, largely on his own. This made for an interesting conundrum. Every VA patient had to have the name of an attending surgeon of record on their chart. Since Devine did not operate, or even scrub in, if we had a big case to do, such as a complex reconstruction, we sometimes had to scramble to find a surgeon whose name we could put on the operating room record as the attending surgeon and, if necessary, to assist us. There were several local plastic surgeons in private practice who maintained privileges at the VA for this purpose. For them, it was a way of maintaining an affiliation with the University of Miami, albeit a tenuous one. It allowed them to legitimately claim the status of Assistant Professor on their resumes, and kept them from being purely cosmetic surgeons. For the most part, they appeared to enjoy working with us and were very helpful. They certainly did not do it for the money since what remuneration there was, if any, was minimal.

Jim Stuzin was one of those young guns. Stuzin had completed his residency in plastic surgery in New York, then gone on to complete two fellowships in craniofacial surgery, one with Wolfe and another craniofacial fellowship with Dr. Henry Kawamoto in California. Like Wolfe, Kawamoto was a protégé of Dr. Tessier. They were close friends and peers with equal stature in craniofacial surgery in the U.S., Wolfe on the east coast and Kawamoto on the west. With this stellar resume, it was no surprise that Stuzin was invited to join the illustrious Baker and Gordon practice. Stuzin clearly enjoyed interacting with the residents and was happy to come over and assist us with complex cases. He looked and acted the part of the cocky, confident, successful young plastic surgeon and I admit to pangs of jealousy at seeing his private practice career effortlessly jump-started working alongside such prominent surgeons as Baker and Gordon. Even so, he was such a nice guy and so quick to help that you could not help liking him.

In addition to Stuzin, I worked with two other young surgeons, Allan Serure and Gary Rosenberg. I was always grateful for these young attendings on a big case, especially one I was doing for the first time. Devine seemed to worry constantly that we would do a big case without an attending present. He kept close tabs on the daily operating room schedule and, if he saw any major cases scheduled for plastic surgery, we could count on him poking his head into the operating room. As soon as he confirmed that we had someone with us, he would look visibly relieved, nod his head in approval, and return to his office.

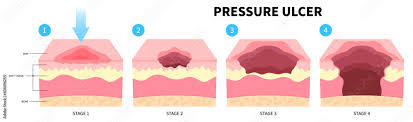

At the VA, there was no lack of patients with bedsores needing debridement and flap reconstruction. These were paraplegics or quadriplegics and their bedsores were invariably huge. Many of the patients had already undergone one or more prior procedures. Each operation narrowed the choice of future options when their bedsore recurred, as they inevitably seemed to do. Finding a flap that had not already been used was sometimes a challenge. At that time, the top reference book for this was McCraw and Arnold’s massive Atlas of Muscle and Myocutaneous Flaps and my copy was well worn by the end of the VA rotation. I would round each week on the bedsore ward and it common to find at least one patient needing, and ready for, surgery. One patient caused quite a bit of excitement.

Tom was a paraplegic who had already had his right leg removed above the knee and now was back with a huge bedsore over his right hip. On one of my weekly rounds, I examined him and found that his hip joint was completely exposed. The remnant of his femur (thigh bone) was barely attached by a few strands of tissue and some dried filaments of the ligaments at the joint. The bone was clearly dead and needed to be removed. Because he had no feeling in the area- a large part of the reason he developed a bedsore in the first place- I set up a small surgical instrument tray at the bedside and, with a few swipes of a scalpel, assisted by a wide-eyed intern, removed the dead femur. I knew this would facilitate his wound care and help prepare the bedsore for closure later with a flap from his thigh. Although the procedure was quite simple, with nary a drop of blood spilled, in the strictest sense what I had done could be called a hip disarticulation. A true hip disarticulation was a bloody, major surgery only performed in the operating room. Somehow, word got back to Devine that I had done a hip disarticulation on a patient at the bedside, and he nearly had a stroke. He urgently called me into his office where it took some careful explaining on my part to assure him that it really wasn’t that big of a deal, but I don’t know if he was fully convinced. From then on, I think he regarded me as a loose cannon, and I suspect he breathed a sigh of relief when I rotated out of the VA.

Devine’s devotion and loyalty to the plastic surgery residency program led him to seek sometimes bizarre ways to expand the influence and scope of the VA’s Division of Plastic Surgery. During my rotation this took a truly strange turn. He decided to establish a foot clinic under the banner of the plastic surgery service and we were expected to staff this. He recruited an orthopedic surgeon with an interest in feet to serve as our supervising attending and assist us in any surgery derived from the clinic. As a result, I had to go to our foot clinic one afternoon per week to see a procession of old, gnarly feet. In my most optimistic moments I could imagine that the clinic was supposed to provide some interesting cases for foot reconstruction but all I ever saw was a collection of corns, bunions, warts, and nail problems of various sorts. Some patients just needed a good toenail trimming, a service we were expected to provide. Unlike his usual habit of staying in his office and leaving the V.A. resident to run the service, Dr. Devine took a hands-on approach to this clinic and never missed a one. The nail clipping was the last straw. After a couple of weeks of this we found numerous excuses to be unavailable for the clinic and, true to the time-honored tradition that rank has its privileges, we would send in our stead a hapless intern or medical student. At the senior resident’s graduation banquet, I gave Devine his own ‘gold-plated’ toenail clippers. To his credit, and my relief, he received this with good humor.

The VA also had its share of project patients who, like Maurice, needed extensive reconstruction spanning many months or years. One of ours was a 65-year-old gentleman whose cancerous penis had been amputated. Penile cancer is an unpleasant disease related, at least in part, to poor hygiene, usually in men who are uncircumcised. Penile reconstruction is a challenge because of the penis’s unique and specific functions in urination and sexual intercourse. Ideally, reconstruction should restore both. At that time, reports were available in the plastic surgical literature offering different techniques to accomplish this. Many cases seemed to be from China, where microsurgery was done seemingly at the drop of a hat, often in situations where a simpler procedure would have served equally well. Microsurgical penile reconstructions involved taking bone, skin, and soft tissue, usually from the forearm, and fashioning a functional penis from this. When successful, it produced an acceptable result but left a very disfiguring donor site scar on the arm. One would have to suppose that most of the patients considered it a worthwhile tradeoff.

For Paul, we took a different approach using a more traditional, some would say antiquated, “tube” flap, like the one I had seen back in medical school. Tube flaps were prevalent during World War II and the Korean War. Dr. Millard had a wealth of experience with them and was a master of this technique. He reported in one of his books how Gillies reconstructed a penis using a tube flap and bone graft. The use of tube flaps has become a lost art in part because newer techniques produce good results with fewer operations. Insurance companies are loathe to pay for multiple procedures and, given the time and labor involved, the reimbursement for surgeons is often not worth the effort. Sometimes, though, they still present a viable surgical option.

A tube flap is created by rolling skin and fat into a long, round tube. Its length, girth, and location depend on the amount of tissue needed and where it will eventually be used. In Paul’s case, we chose the generous apron of loose skin and fat just above where his penis should have been, with the fringe benefit of a modest tummy tuck in the bargain. The flap is done in stages separated by weeks to allow it to slowly adapt to changes in circulation which occur in the process of cutting, shaping, and moving the flap. First, we cut two parallel lines across the lower abdomen and immediately stitched them. These served as a delay of the skin and fat between them, like we did with our scrotum reconstruction in an earlier chapter. A couple of weeks later, we re-cut the same incisions and this time lifted up the skin and fat between the cuts and rolled it into a tube. We closed the skin underneath the tube, which was now attached only at the two ends, much like the carrying handle of a suitcase. The next step was to delay one end of the flap. After waiting several weeks, the tube flap was now receiving most of its circulation from the uncut end and the delayed end could be totally released from its attachment to the body and attached to the base of the missing penis. After a suitable interval, usually six to eight weeks, the other end of the tube could be delayed and subsequently released, leaving the tube hanging from where the penis should be.

In case you’ve lost count, that’s six operations so far, spanning a period of several months. The tube was now where it needed to be, swinging freely, and ready for the finishing touches, such as making the glans. I have simplified the process a bit because, in Paul’s case, we created a tube-within-a-tube so that the reconstructed penis would function for urination. Finally, we planned to add a bone or cartilage graft to stiffen the new penis so that it might function for intercourse. Because Paul was a widower who looked closer to 85 than 65, was obese, and missing most of his teeth, the need for this particular function was arguable, but he was game and no resident worth his salt was going to turn down a patient willing to go through such a challenging and interesting reconstruction.

I first met Paul while working with Dr. Millard on his service. We went over to the VA to help the resident there do the initial creation of the tube flap. Because of the complex nature of this reconstruction and the fact that few plastic surgeons had any experience with tube flaps, Dr. Millard participated in each stage of this case with the resident. At the stage where one end of the tube flap was to be delayed, Dr. Millard was not able to attend but the resident decided to proceed on his own. Apparently, he did not quite grasp the delay concept because, instead of simply making some superficial incisions and sewing them up, he fully released the entire end of the tube, then sewed it back place. He might as well have transferred it to the base of the penis, which he did not do. The tube flap was not ready for such a radical challenge to its blood supply and a large part of the flap broke down. Dr. Millard was not pleased.

My first case at the VA was to salvage Paul’s reconstruction. It took two operations before the flap, a little the worse for wear, was ready for the next generation of residents to, hopefully, complete the reconstruction. I never did see the culmination of all our work. One downside of residency was that you often did not see the end result of procedures that required multiple stages over periods of months. Years later, I attempted to track down someone from the residency who might know the outcome of Paul’s reconstruction. This apparently was lost in the mists of time; I could not find anyone who remembered how it turned out. It may be that he simply grew tired of the process and did not come back to finish or he may have passed away before completion, as he was not in the best of health. Disappointing as this was, my experience with Paul stood me in good stead and I performed several successful tube flap reconstructions later in my practice.

The workload of surgical cases at the VA ran hot and cold and the availability of good cases was unpredictable. Some residents had no lack of work while others found themselves with lots of free time. The generally slower pace of the VA rotation was acknowledged by allowing the VA resident time to see a few patients at Jackson and schedule surgery there once a week. Unfortunately, in the early weeks of my VA rotation, things were very slow. Some residents would check out the VA’s long-term alcohol rehabilitation unit where patients were drying out. These patients were often bored by the enforced confinement and structure of the program. Many were willing, even enthusiastic, volunteers for surgery to fix just about anything; breathing problems from a deviated septum, a bad scar, some visible facial deformity, a non-healing leg ulcer from poor circulation, etc. Residents on their VA rotation could pad their surgical logbook with additional cases from this source, if they chose.

Midway through my VA rotation I became concerned because the volume of cases I was doing seemed insufficient. Dr. Millard clearly shared this concern because he called me in to discuss my progress in training. He hinted that he might not sign my certificate of completion of the residency until I had more operative experience and suggested that I consider spending six months in England to get more operations under my belt after finishing my residency. Dr. Millard had a good friend in England, a plastic surgeon named Malcolm Dean, who would take on residents for such additional training. In England, with its socialized system of medicine, there was no lack of patients waiting for elective plastic surgical procedures.

This was unwelcome news. Having completed a five-year residency in general surgery, and three years of practice in Okinawa, I was older than most of the other residents. The last thing I wanted to do was put my life on hold for another six months, drag my family to England or, worse, leave them behind to undergo yet more training. I was so distraught that day that I could not drive straight home from work and face Sally with this news. I stopped off at our church and shared my dilemma and frustration with my pastor. Although there wasn’t anything he could personally do to affect the situation, he offered a sympathetic ear and a heartfelt prayer that things would change. I hesitate to claim divine intervention but soon thereafter my volume of surgery increased dramatically, so much so that, at the end of my time at the VA, Dr. Millard rescinded his suggestion that I seek additional training and validated my surgical experience for those months.

During my term at the VA, a landmark event occurred across the street at Jackson that passed largely unnoticed by everyone except the plastic surgery residents. One of the new junior residents was Geoffrey Buncke. Yes, the Geoff who had watched his father, Harry, transfer the toe of a monkey to its hand in their garage years earlier. Young Buncke had only three years of a general surgery residency, but he had also spent one year working in his father’s microsurgical unit. He had performed just about every microvascular flap transfer there was, had dozens of cases under his belt as the primary surgeon, and was perfectly at home working through a microscope. He was the stereotypical, laid-back product of California upbringing. Maurice, our Haitian gentleman of the self-inflicted shotgun wound to the face, had returned for another stage of his reconstruction. The Jackson residents were going to rebuild Maurice’s left cheek with a microvascular free flap of skin and bone taken from his left hip. It was the same operation that Wolfe and Banis had performed at Victoria on Alicia.

Because of the novelty, length, and complexity of the case, all the plastic surgery residents who could do so came over to participate and Buncke, the most junior of the group, was our team leader. He was in his element, so relaxed you would have thought what we were doing was routine as we performed what was truly a landmark surgical procedure at Jackson. We worked throughout the day on our own, taking shifts so that everyone could get a chance to scrub in and participate. Buncke assisted me in performing the arterial connection. Although McAfferty looked in on us, neither he nor any other attending was directly involved, even Cassel, the Division’s microsurgeon. The case went without a hitch, the operation was a complete success, and Maurice was one step closer to looking human again.

My final four months of the second year were spent as the chief resident at Jackson Memorial Hospital. I had now come full circle. I was doing my own cases and assisting my junior resident, Bob Hunsaker, with his. I was fortunate to have him. He had just returned from a year of doing plastic surgery in England with Dean while awaiting the start of his residency and was more up to speed than I was when I began. Hunsaker was laid back in contrast to my more intense type A personality. He made those four months a lot of fun.

Given the volume of trauma at Jackson, it was inevitable that we would get our share and some of these were memorable.

Amal, a 7-year-old boy from Egypt, was enjoying a day at the beach with his family when was run down by a boat, The prop of the outboard motor spun down his head and chest. Miraculously, he survived and was brought to the emergency room with a series of extremely deep, parallel lacerations of his scalp, face, neck, and left chest. His skull was fractured, the left half of his face was deeply lacerated with multiple facial fractures, his neck was laid open, and he had a deep, curving laceration into his left chest, through which you could see his left lung and heart. Against all odds, no vital organs were injured. We worked on him alongside residents and attendings from otolaryngology, neurosurgery, and general surgery throughout the night to repair the damage. With the help of Wolfe, Hunsaker and I plated his upper and lower jaw fractures and repaired the extensive facial lacerations. As amazing as was the mere fact of his survival was the fact that no major branches of his facial nerve were severed. Weeks later, I saw him in clinic, and he looked wonderful. The scars were fading and the residual weakness in his facial muscles was already showing visible improvement as evidenced by his broad, slightly asymmetrical smile.

At Jackson, you just never knew where your next case would come from.

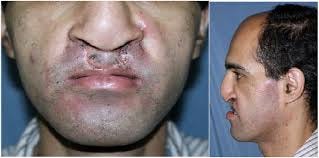

One day, while walking hurriedly through the hospital, I happened to glance into one of the doorways and saw a sight that stopped me in my tracks. Sitting in a waiting room of one of the clinics was a young woman. After a moment’s hesitation, I went in to speak to her. This was my introduction to Luisa, a 30- year-old Cuban immigrant born with a bilateral cleft lip. Something had gone terribly wrong with her surgery in Cuba as an infant and she was left with a severely scarred, tight upper lip, which contrasted greatly with her full lower lip and snubbed nose. Her other facial features were quite attractive with large, dark eyes, full cheeks, and thick black hair but it was impossible to look past the lip and nose. I introduced myself and discovered that she was there for something unrelated to her cleft deformity for which she was not seeing anyone. I offered to see her in our resident’s clinic and a short time later she showed up. I discussed a plan of corrective surgery and she scheduled this without hesitation.

Her problems were deficient tissue in the base of the nose, a tight, a scarred upper lip, and a protuberant lower lip. It was a perfect situation for an Abbe Flap, named for Dr. Robert Abbe, who described it in 1898. Also known as a lip-switch flap, the Abbe flap provided lip tissue from the lower lip to build up a deficient upper lip. I took the scarred area from the upper lip and moved it up to release the snubbed nose. This left a gap in the central upper lip. I marked out my Abbe flap in the center of her lower lip, shaped to match the shield-shaped philtrum of a normal upper lip. Luisa, like many people, had a hint of a dimple in the central lower lip which matched the normal philtrum dimple nicely. I cut this flap free except for the blood vessels on one side to preserve blood flow in and out of the flap. I then rotated the flap and sewed it into the gap in the upper lip. The dual benefit of adding needed volume to the upper lip and reducing the full lower one restored a very nice balance to her lips. It was a perfect example of Dr. Millard’s “Robin Hood Principle” of apportioning tissue so that an area of excess would supply an area of deficiency, thereby benefiting both. It also replaced the upper lip deficiency with tissue as much like it as possible and produced very inconspicuous scars.

For the next week, Luisa’s lips were tethered together by the small artery and vein which kept her Abbe flap alive, and she was limited to taking liquids through a straw. On the eighth day, I took her back to surgery. By now, the flap had enough blood supply from its connections to the upper lip that I was able to divide the blood vessels and separate her lips. A couple of stitches finished the job. Once her scars faded, the upper lip looked almost perfectly normal. Her transformation was astounding. She was so happy that one year later, she drove up from Miami to my practice in Central Florida where I performed a cleft lip rhinoplasty on her to correct some of the nasal deformity resulting from her original cleft lip. The disfigured cleft patient was now a strikingly attractive young woman. It was patients like Luisa who made plastic surgery so fulfilling.

A resident’s time in training is divided between performing surgery, caring for patients in the hospital, seeing patients in the outpatient clinics, and attending, or running, various conferences and assorted meetings. Reading and self-study must be done in whatever discretionary time can be carved out throughout the day and evening between all of the above responsibilities and such annoyingly necessary activities as sleeping and eating. For those who are married, there is the added challenge to find some time for family. Juggling these competing demands makes the classic circus act of keeping a bunch of plates spinning in the air on thin poles child’s play by comparison.

Dr. Millard’s interest in the field of cleft lip and palate surgery made it inevitable that the program at Miami would have a busy clinic devoted to patients with these conditions. Care of patients with cleft lips and palates requires the expertise of multiple specialists because of the many areas affected by these conditions. In addition to the obvious involvement of plastic surgeons to repair the cleft defects, there are several other medical specialties involved, including craniofacial surgeons like Wolfe, otolaryngologists to deal with chronic ear infections, audiologists to assess hearing, orthodontists and dentists to correct dental and bite deformities, speech therapists to help correct speech disorders seen in cleft palates, and child psychologists to help the children and their families cope with the emotional and psychosocial aspects of having such a facial deformity.

Cleft clinic was held one afternoon each week at the Mailman Child Development Center on the medical campus of Jackson Memorial Hospital. Evelyn would pull all the patient charts to be taken over to where the clinic was held. The clinic was run by the chief resident at Jackson, who was responsible for making sure things ran smoothly. Hunsaker and I would go early to see new patients and evaluate the status of current patients, then I would present them to Dr. Millard and the cleft team. The clinic typically ran in the afternoon with a dozen or more patients seen in a couple of hours.

Once our evaluation was complete, we would enter the conference room where Dr. Millard and the rest of the cleft team were assembled. Each patient would be brought in for Dr. Millard to examine as I presented the current status of that patient. Dr. Millard invariably asked the older children about their involvement in sports and would nod encouragingly as they described their activities. Some patients were done in a few minutes, while others might take more time. A plan for future work, if necessary, was made. This might be a touch up of an unsatisfactory lip scar, correction of a nasal deformity, bone grafts to gaps in the upper jaw, or more work on the palate to improve speech. Patients might be sent for braces to realign their teeth, or additional speech therapy as necessary. For some, nothing more was needed beyond setting up a future follow-up visit to be sure they were still doing well. At the conclusion of his examination, Dr. Millard would reach into a bag provided by Evelyn and offer the younger ones a lollipop.

The ultimate reward of cleft clinic for the chief resident came when a patient needed surgery and was assigned to the resident’s service for this. After all the reading and teaching about clefts, and assisting Dr. Millard in these surgeries, we all wanted a shot at doing some of these ourselves. A chief resident was fortunate to have one or two new cleft cases of their own to do during their term. We could count on Dr. Millard to make an appearance in the operating room when we were doing cleft cases. He would come in and look over our shoulder. If things were going well, he might compliment our work. Nothing more than a simple, “nice job,” but we regarded this as high praise indeed. It was always a bit disconcerting to do these cases under the gaze of the surgeon widely acknowledged to be the best in the world at this type of work. One of my treasured mementos from residency is a photograph of Dr. Millard looking over my shoulder as I repaired a cleft palate.

As hectic and stressful as cleft clinic was, it didn’t hold a candle to Grand Rounds. Grand Rounds is a time-honored tradition and all residencies have theirs. This is a weekly conference at which all the residents and attending physicians come together. Although the format varies there is usually a formal program. It may involve a presentation by one of the residents, attendings, or, sometimes, a visiting professor; presentation of unusual or interesting patients; or a combination thereof. In some programs, the attending physicians run the grand rounds. In others, the residents are in charge. In the Division of Plastic Surgery at Miami, Grand Rounds was the chief resident’s baby, and a large part of each week was spent preparing for it.

Grand Rounds attendance was mandatory for all plastic surgery residents except for the resident on the hand surgery service. Dr. Millard and all the other surgeons in the division came. The chairs were arranged in two rows. The attendings sat in front and the residents behind them. Grand Rounds was open to any plastic surgeon who wished to attend, but few plastic surgeons from the community did. This surprised me, but now I appreciate how the demands of private practice make it hard to get away for even a couple of hours per week to attend conferences. I live within an hour of two university medical centers and have never attended plastic surgery Grand Rounds at either of them.

Decades later, I cannot recall many details about my own Grand Rounds as chief resident but two stand out. Grand Rounds was always held on Wednesday morning at eight o’clock in a classroom in the outpatient clinic building. I lived a fair distance from the medical center. In the early morning, before the rush hour traffic set in, I could make the trip one way in about 25 to 30 minutes. During rush hour it could take well over an hour. On this particular morning, in those pre-PowerPoint days, I had prepared a carousel of slides to show at grand rounds. The slides were essential to my presentation. I drove from home to the hospital, parked in the parking garage, and walked toward the classroom. As I approached the classroom door I realized, to my horror, that I had left the carousel on the kitchen table at home. As the realization sank in that, without these slides, I had nothing to present, I broke into a cold sweat. I had to have them. Although Grand Rounds began at 8 AM, I always arrived an hour early in order to set up the projector, review my slides, and organize my thoughts. This cushion still did not give me enough time to get back home and return in time. I would be late; the only question was, by how much? I told Hunsaker, to stall in any way he could and literally sprinted back to my car. The round trip to the house and back was a blur but I have never driven with more attention or determination, weaving through traffic and testing the limits of my little Audi’s maneuverability, not to mention pushing the speed limit more than a little bit. On my return, rush hour was in full force and the glacial pace of traffic was agonizing. I tried not to picture what was happening back in that classroom. I’m sure many people wondered what life and death medical crisis was responsible for the doctor in the white coat sprinting across the medical campus. They had no idea how close they were to the truth, only it was me whose life was in jeopardy, not some patient.

I arrived back at the classroom door at half past eight, caught my breath and stepped inside. Everyone was there, Dr. Millard and all the attendings in the front row as usual, the residents in back. It took me but a moment to put the slide carousel in the projector and begin, during which time no one said a word. No comment was ever made to me about my tardiness nor any inquiry as to its cause. Later, Hunsaker told me that, following Dr. Millard’s lead, the attendings, and all the residents sat there the entire time without exchanging a word as everyone waited for my arrival. I can only conjecture how long this might have gone on. All the residents acknowledged later that, to a man, they were convinced that I was toast. Even today, decades later, I can visualize that classroom, with everyone sitting silently waiting for me, and I must suppress an urge to shudder.

A tradition in our program was to give the chief resident free reign in how to use his final Grand Rounds. Most residents took a conservative, traditional approach and used their last Grand Rounds to show off examples of their work. They would show slides of their most interesting patients and most impressive results before and after surgery. Dr. Millard would acknowledge the quality of the work if it was up to his standards. I chose to do something a little different.

I had come across a short, satirical publication titled, How to Swim with Sharks: A Primer, by the fictitious author, Voltaire Cousteau, published in the American Journal of Nursing in October of 1981. While it was ostensibly about swimming with sharks, it clearly had broader implications and applied to any situation in which one might find oneself in threatening circumstances. It was a perfect theme for my final Grand Rounds and an apt analogy of my residency experience. The primer’s first lines couldn’t have described this better. It read, “Actually, nobody wants to swim with sharks. It is not an acknowledged sport, and it is neither enjoyable nor exhilarating. These instructions are written primarily for the benefit of those who, by virtue of their occupation, find they must swim and find that the water is infested with sharks.”

The primer included such advice as “Assume unidentified fish are sharks- Not all sharks look like sharks, and some fish that are not sharks sometimes act like sharks” and “Do not bleed- It is a cardinal principle that if you are injured, either by accident or intent, you must not bleed,” among others of a similar vein. In 1985, during my time in Okinawa, I had traveled to Australia and had spent eleven days diving on the Great Barrier Reef. As a result, I had a large collection of Kodachrome slides taken on that my dives, including many pictures of sharks. I even had photos of large numbers of reef sharks engaged in feeding frenzies. I interspersed quotes from the primer with my shark slides. From the thinly veiled smiles and quiet chuckles of several of the attendings and residents, the not-so-subtle reference to my residency experience was not lost on them. Dr. Millard was non-committal but I think he appreciated the unusual rounds and my attempt at humor. As he left the room, he turned to me and said, with the slightest hint of a smile, “Nice slides.”

Perhaps the most unique Grand Rounds of all was one presented by Geoff Buncke. Ever the free spirit, Buncke’s final Grand Rounds was the stuff of legend. He chose to show slides of patients on whom he had operated during his tenure as chief, but with a distinctive twist. He set up two projectors so that he could show his before and after slides side-by-side instead of sequentially. So far, so good. Instead of narrating his presentation, however, he embellished his slide show by simultaneously playing the saxophone. To advance his slides, he placed the two projector controls on the floor, took off his shoes and socks, and advanced the slides by pressing the buttons with his toes to the accompaniment of the saxophone. This was one of the few times in anyone’s memory that Dr. Millard was literally at a loss for words!

The remaining months of residency were a blur of long days of surgery, consults, clinics, grand rounds, and reading, always reading. I kept a running log of all my surgeries, as did all residents, to provide documentation of our experience for future credentialing, board certification, and such. Reviewing mine years later, I found that I had been involved in more than 622 operations over those two years. In the first year and when working with Dr. Millard, I had mostly assisted, although I did serve as the principal surgeon on many of them both as a junior resident at Jackson and on the hand service. In my last four months at Jackson, I had done 129 operations either as the principal surgeon or assisting Hunaker. This included 15 facelifts with assorted other facial cosmetic work or nearly one per week (as I said, we did a lot of these). I performed 6 repairs of cleft lips or palates, either primary repairs or revisions of previous work, and 3 microvascular cases of my own. All-in-all, I thought it was a solid experience. When the two years ended, I felt well-prepared to go out and practice as a plastic surgeon.

I left Miami with Dr. Millard’s blessing and, most important, his signature on my residency certificate. In addition, I left the program in his good graces. Not every resident did. I made it a point to correspond with him at least once a year, usually around the Christmas holidays, and wrote to him on several occasions through the years for advice on difficult cases. His replies were brief, but he always replied. I saw him over the years at plastic surgery meetings, including those of the Millard Society, which was comprised of those surgeons who were trained by him or had done fellowships with him. He always greeted me in a friendly fashion.

Up until now, my entire life had been spent in preparation, each chapter simply the next in a series of steps toward my pre-determined goal of becoming a plastic surgeon. When I completed my residency all that was behind me. The future was suddenly here and all that remained was to go out and practice my hard-won specialty. The curtain was about to go up on my professional life.

Richard T. Bosshardt, MD, FACS, Senior Fellow at Do No Harm, Founding Fellow of FAIR in Medicine.

If you have followed my posts, you have come to the end of my book. I hope you enjoyed this. If you would like a copy to keep or give, you can order one from Amazon.