The Making of a Plastic Surgeon- Two Years in the Crucible Learning the Art and Science

Chapter 6- Victoria Hospital (and first exposure to craniofacial and microsurgery)

(After a brief holiday hiatus, here is the next chapter of my book for those who have gotten this far. RTB)

“The high-pitched whine of the power saw, the metallic sound of the hammer on the chisel, the cracking sound of fracturing bone, and the sound of the drill to place the steel plates in these cases seemed more appropriate to a construction site than an operating room.” The Making of a Plastic Surgeon

By the end of the second month of residency, my immersion in the specialty was complete. General surgery had receded into a seemingly distant past life. I was feeling more at ease and comfortable back in residency. Of course, as with all residencies, just when you began to feel comfortable, it was time to move on to the next rotation.

Leaving the resident’s service at Jackson after two months, I entered another world: the world of private practice plastic surgery. This was our rotation at Victoria Hospital, just a few miles down the road from Jackson, but a world away socioeconomically. Until this moment, I had minimal exposure to the private practice side of medicine. Even though medical students rotated at certain private hospitals in the greater Miami area, and I did the same during some outside rotations while at Oak Knoll, I had never actually spent any time in a private practice setting. All my time after medical school was spent in military hospitals and university teaching hospitals much like Jackson. This was about to change.

On the Victoria service, we worked primarily with Tony Wolfe and Buster Mullin. Although both were clinical professors in the Division of Plastic Surgery, they were in full time private practice and did not derive any income directly from their academic positions. All of the attendings in the Division of Plastic Surgery except for McAfferty and Devine shared office space in an impressive two-story building tucked away on a quiet, shaded street a few blocks from Jackson. The entrance was guarded by two large, stone lions. The building was owned by Dr. Millard and the others leased their offices from him.

As with most medical offices the walls were covered with the usual collection of diplomas, framed certificates, testimonials from grateful patients and the occasional autographed photograph of some notable personality who had been a patient of one of the attendings. One of those was the late Jackie Gleason, the famed Miami Beach entertainer and star of the once popular television comedy series, The Honeymooners. Known locally as “The Great One,” Gleason had signed his photo, “To Doc Millard, The! Absolute!! Best!!!” Dr. Millard had corrected Gleason’s droopy eyelids a few years earlier. There was also an extensive gallery of photographs of those surgeons who had trained at Miami. Someday, I hoped, I would join them.

The clinic situation in the office was one that I had never encountered. Every surgery clinic I had ever worked in ran similarly. Residents would see patients, either on their own or under the supervision of a more senior resident or an attending surgeon. The patient flow would be steady and there was usually very little down time except for a short lunch break. The Victoria rotation was very different. We did not see any patients on our own. We would linger in the hall and only enter exam rooms to see a patient when the surgeon did. Although we were not actually working with Dr. Millard, he would sometimes call us into an exam room to see one of his patients if the case was interesting.

Compared to the resident’s clinic at Jackson, with its largely bare walls, rudimentary furnishings, and noisy clamor of crowds of mostly foreign patients, the cool, quiet, and refined environment of the office was a welcome change, at first. It wasn’t long, however, before I began to miss the former. It seemed to me that we spent an inordinate amount of time standing around in the hall waiting to see the next patient. We did not really participate in any of the surgical decision making and our interaction with the patients themselves was largely limited to completing their paperwork for future surgery. I never felt a real connection to any patient that I saw during that time.

Wolfe and Mullin were on staff at the multiple hospitals around the medical center including Jackson, the VA, and Cedars of Lebanon but their primary hospital was Victoria. The cosmetic patients at Victoria paid for their surgery. With a few notable exceptions, every reconstruction patient in Victoria had some form of medical insurance; patients on Medicaid, the state-funded insurance for the indigent, or patients with no insurance at all, went to Jackson. Just walking into the hospital lobby underscored some of the differences. Victoria’s was more reminiscent of a nice hotel than a hospital. Most of the rooms were private. The pace on the Victoria service was considerably slower than at Jackson. Lunch was often a leisurely affair in the doctor’s private lunchroom, which put Jackson’s bustling cafeteria to shame. If the surgery day finished early, Tony would sometimes take us to a dilapidated seafood shack on the Miami River downtown that served up terrific, fresh grouper sandwiches. We were not subject to being called for emergencies while at Victoria.

Whereas at Jackson, the plastic surgery residents pretty much ran the show and did nearly all the surgery, at Victoria we only assisted in surgery. Having worked exclusively with the chief resident for two months, observing the attending surgeons was a revelation. It was the medical equivalent of going from amateur to pro in a sport. The culmination of years of experience made them very proficient and, in the case of Wolfe, very fast.

The variety of surgery ranged from straightforward skin cancer excisions to fantastically complex craniofacial reconstruction. This was my first exposure to the subspecialty of craniofacial surgery. Craniofacial surgery involved operating on the skull and facial bones for the purpose of correcting deformities that were present at birth, arose from abnormal growth and development of the head, or were the result of traumatic injuries or surgery for conditions such as cancers of the head and neck. This anatomical area is uniquely complex. There are 14 bones ranging from the lower jaw to the tiny bones in the inner ear. The sheer concentration of vital structures in this relatively small area exceeds that of any other part of the body. The three-dimensional complexity of the area demands meticulous planning and precise execution of any surgery. The incredibly rich blood supply of the head can make even minor surgery potentially very bloody. Taken together, these present a formidable challenge for both cosmetic and reconstructive surgery.

It is not often that an entire subspecialty of surgery can be ascribed to one person, but such is the case with craniofacial surgery. It is universally acknowledged to be the legacy of a French plastic surgeon, Paul Tessier. In the 1950’s, Dr. Tessier began his efforts to improve on the results of operations on the facial skeleton to correct birth defects from such conditions as Crouzon Syndrome, Apert Syndrome, Pierre Robin Syndrome, and a host of others. Children born with these conditions all have severe bony deformities of the face with issues ranging from just looking weird to difficulties breathing and problems with brain development.

Operations to correct these conditions are among the most complex operations in all of surgery. To reshape the face, the bones must be cut or broken in order to move them into normal position while preserving critical structures. These include the eyes, nerves, vital arteries and veins, teeth and their roots, sinuses, the nasal and oral airways, and, of course, the brain. In children, the surgeon must consider the effects of surgery on future growth and development of the face. Prior efforts, including those of Sir Harold Gillies, who was also a mentor of Tessier, produced disappointing results because the facial bones often gradually shifted back to their former position. Tessier devised innovative ways of cutting and moving the bones safely, then bridging any gaps thus created with pieces of bone to avoid relapse. These were either taken from cadavers or living bone grafts were harvested from the patients themselves. This was another example of Dr. Millard’s principle of moving things into normal position and retaining them there, which was a critical feature of his cleft lip repair. Like Dr. Millard’s cleft lip repair, Tessier placed his surgical incisions in such a manner as to produce the most inconspicuous scars possible.

Tessier’s results were so remarkable that surgeons came from all over the world to learn his techniques. These could also be applied to the treatment of severe facial trauma and became the standard for that as well. He was truly the father of the specialty of craniofacial surgery and all surgeons performing this type of work today were either trained by Tessier himself or by one of the many surgeons who traveled to France to learn from him.

Wolfe was one of the best known of Tessier’s protégés. Although the residents all called him “Tony”, this familiarity in no way diminished the respect with which we regarded him. A brilliant, extensively published, and internationally renowned surgeon in his own right, Wolfe had trained in plastic surgery under Dr. Millard and then traveled to France to work with Tessier before returning to Miami to begin his practice. He had dark, piercing eyes above which were wild, busy eyebrows. Fluent in several languages, he was one of the most respected and sought-after craniofacial surgeons in the world. In addition to his role as an attending in the residency program at Jackson, Wolfe offered a six-month fellowship to plastic surgeons seeking additional training in craniofacial surgery after completing their residency. The fellow served as his first assistant on all his craniofacial cases. We served as second assistant, or sometimes simply watched the surgery from behind the anesthesia screen without scrubbing in. Despite this constant flux of fellows with varying levels of skill and abilities assisting him, Wolfe was still one of the fastest surgeons I have ever seen and his confidence and the ease with which he surgically manipulated the bones of the face never ceased to amaze me.

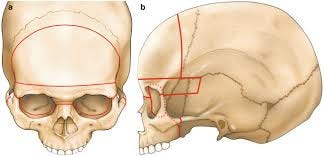

One of the first craniofacial cases I scrubbed in on was that of 7-year-old Adam. Adam, had Crouzon Syndrome, an inherited disorder resulting from a gene mutation. The normal infant skull consists of several bones that are disconnected at first. This “floating” arrangement allows for growth of the brain and normal facial development during infancy. In Crouzon Syndrome several of the bones fuse prematurely causing growth disturbances and several visible abnormalities. Adam’s eyes were set much too far apart. His eye sockets were also too shallow, such that his eyes bulged to a point where he was unable to close them fully. This can cause dry eyes, ulceration, and even blindness. Like all children with Crouzon’s, Adam, looked weird, with his frog-like eyes, flat cheeks, jutting lower jaw, and oddly shaped head.

Wolfe made cuts around the bony orbits, which contain the eyes, separating them into two individual blocks. He then removed the excessive bone between them. He also made cuts to release the upper jaw from the skull. The bone cuts, called osteotomies, were done with a combination of power saws and fine chisels. The high-pitched whine of the power saw, the metallic sound of the hammer on the chisel, the cracking sound of fracturing bone, and the sound of the drill to place the steel plates in these cases seemed more appropriate to a construction site than an operating room. At times I thought we should be wearing hardhats rather than our surgical caps. Wolfe was truly in his element in these cases, cutting bones, moving them around, and inserting tiny plates and screws with a level of confidence, dexterity, and alacrity that had to be seen to be truly appreciated. In securing the upper and lower jaws with arch bars, as was often necessary, he could do in minutes what would have taken me an hour or longer. The 3-dimensional, spatial nature was unique to craniofacial surgery and Wolfe was at the forefront of using 3-D computerized axial tomography (CAT) scans in planning his surgery. For many patients he had plastic, molded splints pre-made to properly align the teeth and help hold them in their new position temporarily.

In Adam’s case, once the excess bone separating them was removed, the bone blocks containing his eyes were then shifted closer together. At the same time, the upper jaw was also cut and pulled forward to deepen the eye socket. Wolfe secured the bones in their new position with titanium plates and screws and then harvested bone grafts from Adam’s hips to fill in the gaps. Once these healed and solidified, the position of the bones would be secure. When Adam left the operating room, despite the swelling and bruising from the surgery, he looked almost normal for the first time. The change was astonishing.

One of the Tessier’s principles of craniofacial surgery that Wolfe adhered to was the superiority of bone grafts over the use of other biologic and non-biological materials in the face. Synthetic implants had an annoying tendency to erode through the skin over time or shift from their intended position. If an infection occurred in the presence of an artificial implant, the implant invariably had to be removed. Some implant materials used in place of bone were essentially purified fragments from coral. These had several shortcomings. Artificial bone substitutes were limited to only certain uses and sometimes broke down over time. They did have the advantage of being readily available and easy to use.

Wolfe was firmly in the camp of those craniofacial surgeons who advocated for harvesting living bone from the patient to be used for bone grafts, a process called autologous bone grafting, whenever possible. Autologous bone would not be rejected. It would heal solidly, would be permanent and resistant to infection later. Bone grafts could even grow with the patient. There were many potential donor sites for bone grafts. The downside was the additional surgery to harvest a patient’s own bone.

Many surgeons balk at the additional surgery to obtain bone grafts because of the extra time, effort, and small added risk. A lot of plastic surgeons simply are not comfortable working with bone. Autologous bone grafts were second nature to Wolfe. He could harvest a bone graft almost effortlessly and his speed was such that his operations using bone grafts usually took no more, and often less, time than other surgeon’s operations using artificial materials. In the time it took some surgeons to insert a silicone chin implant to augment a weak chin, Tony could saw through the bone of the chin, shift it forward for the desired correction, and secure it with some plates and screws. I saw him do this many times. He made it look easy.

Walter “Buster” Mullin was a more low-profile member of the Division. He had also trained under Dr. Millard and then gone to Scotland for additional training after his residency. He had an extremely busy cosmetic practice. In the operating room, his was a calm demeanor and he demonstrated a wonderful technical proficiency that I hoped to someday achieve. I never saw him angry or upset and the operating room environment during his cases was always relaxed and pleasant. Mullin was more engaging than Dr. Millard or Wolfe and did not exude their intensity. While he had published his share of papers, it was clear that he was perfectly content to practice in relative obscurity compared to the other two. In a division largely devoid of these traits, he was a uniquely warm and friendly presence and the attending surgeon with whom I felt most comfortable.

Mullin’s practice included a heavy preponderance of breast surgery, both cosmetic and reconstructive, and we regarded him as a master of breast surgery. I always enjoyed assisting him on breast cases and most of what I learned about breast surgery in my residency I learned from him. He excelled in breast reductions and some of his results were the best I have seen.

John Cassel was the newest and youngest member of the Division and rounded out the attendings who were most actively engaged with the residents on the Victoria rotation. As one of the older members of my medical school class, Cassel had been part of what we referred to as the “geriatric squad.” Unlike those of us who were in our twenties, they were all thirty-something and older. After graduation, he did three years of general surgery training and a plastic surgery residency with Dr. Millard. Once he completed that training, he headed off to California to do a fellowship in microvascular surgery under Dr. Harry Buncke, the acknowledged dean of microsurgery in the U.S.

The history of microsurgery is an archetypal American success story of rugged individualism, ingenuity, industriousness, optimism, and dogged persistence. In the 1950s the idea that surgeons could actually sew blood vessels less than a millimeter in diameter together and establish blood flow across the connection was so outrageous that few surgeons were even investigating the possibility. Buncke, a plastic surgeon in San Francisco, was fascinated by the possibilities and potential of microsurgery and resolved to make this a reality. Unable to obtain funding for his work, he set up a makeshift operating room in the garage of his home. At that time there were really no instruments commercially available that were suitable for the delicate work of microsurgery, so he designed and made his own. In addition, there were no sutures or needles fine enough for this type of work. Because even the tiniest existing needles were too large, he learned how to heat the tips of fine silk filaments, thinner than a human hair, to metallize them into tiny needles.

He worked in his spare time perfecting his techniques in this garage, often with his wife assisting and children looking on. In 1964, after fifty-one failed attempts, he reported the successful re-plantation of a rabbit’s ear in the British Journal of Plastic Surgery. It was the first time anyone had successfully sewn together blood vessels smaller than one millimeter.

In 1966, still in his makeshift garage operating room, Buncke successfully transplanted the toe of a rhesus monkey to its hand. His wife, Constance, a dermatologist, assisted him while his youngest son, Geoffrey, looked on. In 1969, working with Navy surgeon Don McLean, Buncke used his microvascular skills to transfer omentum, a mass of fatty tissue from the abdomen, to cover a large scalp wound in a patient at the Oakland Naval Hospital where I would train nine years later. In 1972, Buncke performed the first microsurgical toe to thumb transplant on a firefighter for the City of Redwood, California, which allowed him to return to work. There were many other firsts over the subsequent years. From these humble beginnings, the subspecialty of microsurgery grew to become an important part of the specialty of plastic surgery. In 1970, Buncke opened the microsurgery unit that now bears his name at the Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco. He trained hundreds of microsurgeons in the U.S. and abroad.

Once he completed his yearlong microsurgery fellowship with Buncke, Cassel returned to Miami. He almost did not make it much past his return from California to start his practice. He was involved in a horrific automobile accident that almost killed him. The accident damaged nerves in his right arm and almost derailed his career as a surgeon. He overcame this with tremendous drive and effort over many months of rehabilitation.

In the 1980s microsurgery was still a relatively young subspecialty with few trained practitioners. Cassel was in high demand and operated out of more hospitals in the greater Miami area than any of the other attendings. Cassel was methodical and deliberate, which was a nice way of saying slow. His slower pace in surgery was a stark contrast to Wolfe’s speed. Micro cases were tedious and exacting and they sometimes occupied the better part of a day. Eight or more hours in surgery was not unusual. As with the other operations on the Victoria rotation, our role was relegated to assisting only. Assisting Cassel under the microscope for hours on end could be tedious and boring and his call for a resident to help him on one of these microvascular cases was often met with a distinct lack of enthusiasm. I enjoyed the micro cases. The exacting nature of the surgery appealed to me. I also enjoyed working with a former classmate. Cassel was a kind and gentle soul and tragically passed away suddenly in 2015.

Working at Victoria was a bit like lining up at a daily buffet of plastic surgery procedures. Each afternoon, I would look at the operating room schedule for the next day and choose the cases I planned to scrub in on or observe. Wolfe might have a major craniofacial reconstruction scheduled, some other reconstruction, or a cosmetic case or two. Mullin might have one or more cosmetic or reconstructive breast cases, some other cosmetic work such as an abdominoplasty (tummy tuck) or brachioplasty (arm lift), or a facial reconstruction after removal of a large skin cancer. On occasion, Cassel would weigh in with a case of his own at Victoria or some other hospital in the greater Miami area. When Wolfe had a craniofacial case, we knew that would occupy much of a morning; these cases were lengthy despite his speed. We also knew we wouldn’t get to do very much besides watch as his fellow would serve as first assistant. On the other hand, he might have a facelift or some other cosmetic procedure and his fellow would typically allow us to first assist. Wolfe’s speed carried over from his craniofacial work to everything else he did. Once, I assisted him on a full facelift, usually a three-to-four-hour procedure. As we put in the final suture, I looked up and saw that we had completed this in barely two hours.

If Mullin had cases scheduled, I was always tempted to work with him. He was an excellent teacher and I always enjoyed assisting him in surgery. He had a very busy breast practice and his operating room schedule included many breast augmentations, reductions, lifts, and reconstruction. I found that I really enjoyed breast surgery and if he had a breast reduction scheduled, it was usually an easy decision to choose to assist him. His cosmetic practice was also very busy with facelifts and other facial cosmetic procedures, and body contouring, such as abdominoplasties. His facelifts rivaled those of Dr. Millard. Given his skill and personality, it came as no surprise that a number of local plastic surgeons chose Mullin for their own cosmetic surgery or that of their wives.

By the end of these first four months, I felt like I was just beginning to understand the scope of my chosen specialty. I was anxious to return to the resident’s service at Jackson to apply what I had learned and try my hand at some of the procedures I had observed. First, though, I had a small detour to take. My horizons were going to be expanded further as I left Victoria and moved to the Division of Hand Surgery at Jackson in the Department of Orthopedics.

Richard T. Bosshardt, MD, FACS, Senior Fellow at Do No Harm, Founding Fellow at FAIR in Medicine.

For those who want to read ahead, you can order your copy of my book on Amazon as an eBook or paperback.

Excellent work Rick, and great writing. If I ever trained to be a plastic surgeon, I would want to have read your book as part of my education and training. Thanks for giving back.