The Making of a Plastic Surgeon- Two Years in the Crucible Learning the Art and Science

Chapter 8- Working with Dr. Millard

Few people are privileged to train under someone who is considered the best in the world at their profession. Against all probability that is the situation I found myself in when I was selected to train under Dr. D. Ralph Millard, Jr. His peers rated him among the top ten plastic surgeons of the millenium. My four months working directly with him were ones I will never forget.

“Uh, Houston, we have a problem.”

Jim Lovell in Apollo 13

My four-month block working with Dr. Millard ran from May through August 1988, right in the middle of the two-year residency. I worked one-on-one with Dr. Millard as his surgical assistant on all of his cases, rounding on his patients at the hospital, and seeing new patients with him in his office. Though seldom approached without some trepidation, it was generally regarded as the highlight of the entire residency, and given Dr. Millard’s stature, a rare privilege. By now, I felt I knew enough about plastic surgery that I wouldn’t completely embarrass myself.

It was a long-standing tradition for residents to pass on the accumulated wisdom of the past to the new kid whose head was about to go on the chopping block. Knowing these little details immeasurably relieved some of the anxiety of approaching this watershed time during our training and saved many a resident considerable grief. Dr. Millard expected that each new resident to his service would transition smoothly and immediately mesh seamlessly into his routine without any interruption in the efficient execution of the surgical schedule.

Working with Dr. Millard could be stressful. One resident who came before me was assisting him on a cleft lip. Dr. Millard would sometimes act as though the case he was doing was the most complex and difficult case he had ever done and complained from start to finish. A group of visiting Japanese plastic surgeons was in the operating room observing. Dr. Millard was berating the resident. “No, hold the hook this way, not that way. Try to help me!” “My God, I can’t teach you anything!” “You are making this more difficult than it needs to be!” The stream of invective continued unabated the entire case. After the operation was finished, Dr. Millard left the room and the resident hunkered down in a corner, writing postoperative orders and nursing his bruised ego. One of the Japanese doctors quietly approached and gently tugged at his sleeve. He looked up. “You not so bad,” said the visiting surgeon sympathetically in heavily accented English.

You could say that my first day with Dr. Millard did not begin auspiciously. On the first case of the day, he was repairing a cleft palate and working down in the mouth of a small child. I leaned in to try to get a better look at what he was doing, and the protruding lens of my headlight lightly bumped his head. He stopped what he was doing, laid down his instruments, leaned back on his stool, and looked up at me with that steely gaze.

“I can see that you and I are going to have a problem.”

“Sorry. Won’t happen again.” I said and we returned to work.

Surgery in Dr. Millard’s room was a business-like affair which brooked no interruptions. When working with him you were a quick study, or you were toast.

Dr. Millard’s practice was unique in many ways. His cosmetic surgery schedule was fully booked as much as two years in advance. There were only a handful of surgeons in the world who commanded such respect and were in such demand that patients would wait that long for their surgery. I am happy if my surgical schedule is filled a couple of months down the road. His consultations were brief and to the point. If there was any aspect of the patient’s circumstances he did not like, the consultation was over, and they were told to find another surgeon. I saw patients literally beg him to change his mind. I daresay few plastic surgeons will ever know what this is like. After he left the room, some patients would plead with me to intercede on their behalf. This was flattering but we residents had no influence on Dr. Millard’s patient selection or surgical decision-making. For patients who were scheduled for surgery, once their number came up, it was our job go over the surgical plan with them, obtain their signed consent, perform a cursory general physical examination, complete all the necessary paperwork, and basically cross all the “t’s” and dot all the “i’s” to get them to the operating room. We took care of them after surgery, removed dressings and sutures, and instructed them on aftercare as well. Essentially, we did everything but the operation itself.

In a moment of unusual candor, Dr. Millard admitted to me that he appreciated having residents liberate him from having to deal with all those extraneous details in dealing with the cosmetic surgery patients. It was obvious that cosmetic surgery was a distraction from his main interest, which was clearly reconstruction. He always seemed to be a little more abrupt and impatient with the cosmetic patients.

This was exactly the opposite of his demeanor with those who came in for reconstructive surgery, especially the children. This is not to say that he did an about-face and suddenly radiated warmth and friendliness, but the difference was obvious to those of us who worked with him. His intense interest and total involvement in these cases was clearly evident. He would take time to speak to the older kids and always inquired about their involvement in sports. He never seemed rushed with children and when his temper and impatience were manifest it was usually the result of some interruption in the flow of the clinic, a delay in treatment, or when the results were not to his satisfaction, never with the patients themselves.

The angriest I ever saw him was after he repaired a cleft lip on a baby whose family lived on the West Coast. All went well and, on the day I removed the sutures, the parents and baby flew back to California. Twelve hours later, he received a frantic call from the parents. In a moment of inattention, the baby had bumped his face and the lip had split open. I only heard Dr. Millard’s side of the telephone conversation but it was clear that his anger at this careless lapse was barely contained as he instructed them to see one of his former residents out there to have the lip sutured. He could not believe such carelessness and was in a foul mood the rest of the day.

Although known for his innovative style and constant striving to improve his techniques, after decades of practice, he was also very set in certain routines. His facelifts exemplified the importance of a smooth passing-of-the-baton among the residents and were choreographed as precisely as any Broadway stage production. All were done under local anesthesia with intravenous sedation provided by an anesthesiologist. The patient’s face was prepared by Ellen, his nurse, and then draped by him in the same manner, every time. Dr. Millard injected local anesthetic into the face after the patient was sedated and the resident put pressure on each area in turn to minimize swelling and bruising from the injections. As he incised and elevated the facial skin, the resident would retract the skin with fine hooks to provide exposure while simultaneously using the electrocautery hand piece to coagulate any points of bleeding. This had to be done in such a fashion so as not to obstruct or delay Dr. Millard, even a little. When suturing began, the resident would cut sutures for him while simultaneously doing some of the suturing as well. We became adept at juggling these two things at once. All this was done without a word being exchanged and woe to the resident who slowed things down by being unprepared or failing to keep pace with him.

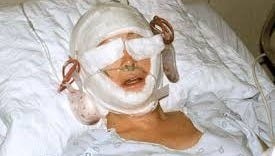

His facelift dressing was a model of consistency, put on the same way each time, the gauze pads applied in the same order and the wrapping performed in the same direction. It was an excellent dressing, placing gentle, even pressure over all the areas of surgery to minimize bruising and swelling. I still use it today.

In patients who underwent simultaneous eyelid surgery with their facelift, once the facelift dressing was in place, he would add a second dressing by putting eye pads over each eye and securing them with additional wrapping, again to minimize bruising and swelling. Dr. Millard kept his facelift patients overnight in the hospital. It was the resident’s responsibility to go up to the patient’s room later that afternoon to remove the dressing over the eyes so it would not stay on all night. The facelift dressing, however, was left undisturbed until the next morning, when it was removed to inspect the face and remove the drain tubes. A new face dressing was then applied to be removed several days later in the office at the first postoperative visit. We would sometimes finish a facelift, see a few patients in clinic and be done by one or two in the afternoon. This would leave me hanging around the medical center until 4 or 5 o’clock for no other reason than to remove the eye pads. It seemed such a waste of time that I came up with a simple solution. I tried it on the next patient.

After all the dressings were placed and Dr. Millard had left the operating room, I added one more postoperative order to the chart. I instructed the nurses on the ward to remove the eye dressing that afternoon. To avoid any possible miscommunication, my order was precise. I specified the time of removal and clearly stated that only the dressing I had marked was to be taken down. I marked the eye dressing clearly with big purple “X’s” using a skin marking pen so there could be no confusion as to which dressing was to be removed. Foolproof, right? I arrived home early that day, much to the surprise of Sally and the kids. I was proud of my efficiency and feeling pretty smug.

The next morning, I arrived at the hospital early, to see the patient in advance to make sure all was well and expedite our morning rounds. Little suspecting the ambush that awaited me, I walked into the room and was horrified to see her sitting up in bed with no dressing whatsoever. Her drain tubes stuck out like weird antennae. The evening nurse had, for some unfathomable reason, removed the entire dressing, not just the eye pads. Fighting panic, I composed myself and calmly walked out to the nurse’s station to ask for help in putting a dressing back on. I had no idea how much time I had before Dr. Millard arrived, but I knew it could not be more than a few minutes. Gathering the necessary supplies seemed to take forever. As I did so, I contemplated the potential implications of my situation.

I could see my fledgling career as a plastic surgeon crashing and burning before it ever really took flight. My actions to save myself a little inconvenience, when I viewed them from Dr. Millard’s perspective, took on the flavor of a gross dereliction of duty. Just as I could not let the nurses know that I was in a state of total panic inside, neither could I let on to the patient that all was not as it should be. She, however, was pretty sharp and quickly caught on to my predicament. Thankfully, she was not only understanding but, when I asked her not to say anything about the dressing coming off that night, she did not bat an eye. If this had been a movie, the scene would have jumped back and forth from me, desperately trying to reassemble and reapply a new dressing, to Dr. Millard, arriving at the hospital, ascending on the elevator, and walking toward the patient’s room. A suspenseful soundtrack would definitely have played in the background, rising to a crescendo as the two scenes converged. Would I make it, or would he walk in on me before I was done? How would he react? The timing could not have been closer. He arrived seconds after I finished. I tried to remain outwardly calm, giving no hint of my furious activity just moments earlier. I now undid the dressing that I had just finished placing a moment earlier, removed her drains, and applied another facelift dressing after he had inspected her and pronounced everything satisfactory. Whether he suspected or not I’ll never know for sure. It may occur to the reader to ask why I did not simply act as though I had just removed the dressing before Dr. Millard arrived rather than go through the Chinese fire drill of putting on a new dressing only to remove it a moment later. The simple answer is that I was so panicked that thought never occurred to me. Also, it was not part of the standard routine for me to do this. Dr. Millard never let on that he suspected anything was amiss and the patient, bless her, never said a word. As we turned to leave, out of the corner of my eye, I swear I saw her give me a conspiratorial wink.

Once a week, Dr. Millard would operate across town at the Miami Children’s Hospital. There was a well-established ritual which was followed on this day. After morning rounds at Jackson we would return to his office. From there we would depart in his car for the round trip to Children’s. Dr. Millard drove a late-model Cadillac Seville and, as he approached the car, would always turn the keys over to the resident, who then drove the car to the hospital and back with the boss riding shotgun. My Audi Fox was quite compact and maneuverable, and I was used to zipping around town. Not here. Not since driver’s education classes in high school have I paid closer attention to my driving,

The return route from Children’s Hospital back to his office included going through a toll booth with a toll of 25 cents. I knew from my briefing by the previous resident that Dr. Millard would pay the toll, but I wondered if I should not at least make a gesture of paying on the first day. I mulled this over in my mind at various times throughout the day to the point where, even during surgery, I found my thoughts turning to just how to handle this. Having considered and reconsidered offering up the toll when the time came, I decided that I should probably at least make a show of paying. As we approached the toll booth, I tried to reach into my pants pocket only to realize that my white lab coat, with the seat belt and shoulder strap on, prevented me from getting to it. As I struggled, Dr. Millard leaned over with a quarter in his hand, handed it to me, and said, “Anticipation.” One word, but pregnant with meaning. I knew immediately what he meant. I should have anticipated the toll booth and had my money out ahead of time, not waited until the last minute. Anticipation was a quality highly valued in a surgical assistant in knowing each step of the operation and anticipating the surgeon’s needs for retraction, cautery, instrumentation, suction, sutures, etc. Anticipation was an important quality for a surgeon also, looking ahead in each operation for areas of potential difficulty or problems. The rebuke stung all-the-more coming as it did on the heels of an entire morning and part of the afternoon doing just that, anticipating. I wanted to shout, “Dr. Millard, I am a 36-year-old, board-certified general surgeon with three years of practice experience. I have just spent the better part of my day wondering whether or not to pull out this stupid quarter, and now you’re telling I should show more anticipation??!!” Fortunately, discretion prevailed over my desire to set the record straight and I said nothing.

Given Dr. Millard’s vast fund of knowledge in the field of plastic surgery, we could count on being routinely grilled about the cases of the day or any aspect of the specialty and its history. If we couldn’t answer a question, we knew to look it up that evening and have an answer the next day. Although I read constantly, the specialty was so broad that I could have read non-stop for the two years and still not covered all the pertinent material. I never even finished reading all of Dr. Millard’s books and journal articles from beginning to end.

Dr. Millard assumed that his residents would have sufficient surgical experience prior to entering his residency that they would have a strong foundation of basic surgical technique and sound surgical judgment on which he could build. His contribution was to add his principles and the residency provided endless opportunities to apply them. One of his requirements of the resident on his service was that they make out 3 by 5-inch cards in advance of each day’s surgeries. The cards were to include our plan for each case broken down step-by-step. The applicable principle or principles for each step were to be written down as well. These cards were reviewed Monday morning at breakfast before the week’s surgery schedule began. During my first couple of weeks working with him, I was not asked for my cards. Predictably, on the first day I did not have them with me, he asked. I felt like a kid in school being reprimanded for failing to do my homework. Dr. Millard was a stickler for principles and their proper application in planning and execution of surgery. Many of us did not fully appreciate it then, but this emphasis was intended to produce plastic surgeons who would be as meticulous and compulsive as he was. He wanted this application of principles to become our default mode in planning and performing surgery. This was itself one of the principles he espoused and included in his book. The adherence to principles, whether implicit or explicit, was an element of all surgery, but the degree to which it was stressed in our training was altogether unique in my experience.

The resident on Dr. Millard’s service did not have emergency room responsibilities and the weekly schedule was not overly taxing. It was the resident’s responsibility to field all calls from Dr. Millard’s patients after hours and on weekends. Fortunately, these were infrequent, but some were interesting. Although I never knew what he charged for cosmetic surgery, given his reputation one would assume most of his cosmetic patients would be from the wealthier strata of society. Surprisingly many seemed to be rather regular folks. Sometimes residents made house calls to check on a postoperative patient. I did this on one lady after her facelift. She was in her 60s and lived on Miami Beach. I was surprised to pull up in front of a small, old stucco house located in a surprisingly shabby neighborhood. The small yard was unkempt. The house was not air-conditioned and the frosted-glass jalousie windows were cranked wide open in the midday summer heat. Inside, it was stifling and just as humid as outside. She was wearing a loose one-piece house dress, stained with sweat. Happily, she was doing well and my time in that oven was mercifully brief. I could not help but wonder why she felt the need for cosmetic surgery, what led her to Dr. Millard, and how she managed to pay for this.

Dr. Millard’s international reputation drew a constant stream of plastic surgeons from all over the world to Miami to observe him for anywhere from a few days to several months. Dr. Millard took in one plastic surgeon per year for a three-month fellowship. The fellowship came with a small stipend to help cover expenses and was funded by a variety of grants and endowments. The list of those who undertook these fellowships was a veritable Who’s Who of well-known plastic surgeons. Dr. Millard had little patience for small talk and was sometimes frustrated with the difficulties in communicating with some of the foreign physicians. A visiting surgeon from Korea, asked several questions in broken English before Dr. Millard suggested that he go back to Korea and return when he had a better command of the language. One surgeon, from Germany, asked Dr. Millard what suture he was using and was answered with an incredulous look.

“You came all the way from Germany to ask me what suture I am using?” he said. The poor fellow was taken aback and did not know how to respond. I knew how he felt. As I said, sometimes Dr. Millard could be difficult to like.

Because my four months with Dr. Millard straddled two academic years, he had two fellows during that period. One was an experienced plastic surgeon from Korea. Kyung Kim’s English was heavily accented but passable and he and Dr. Millard got on well. Dr. Millard always invited every resident to dinner at his home during the four-month rotation with him. My invitation came at a time when Mrs. Millard was off in North Carolina for the summer. Kim was invited as well. Sally had never met Dr. Millard face-to-face. Kim’s English was simply not up to making dinner conversation and I was just too nervous and uptight to carry the load alone. Dr. Millard lived in a stately, colonnaded home in a gated community on Biscayne Bay. His maid prepared a lovely dinner of lamb, which we ate in the formal dining room before moving to a sitting room. There were many moments of awkward silence during and after the meal. Although I am sure Dr. Millard did his best to be a gracious host, I just could not make the transition from resident to dinner guest and was relieved when the evening was over.

The other fellow was Mary Lyn Lu, a Chinese-American plastic surgeon just out of residency. She was the only female Dr. Millard ever accepted, either as a fellow or as a resident. Why she made the cut I do not know, but she clearly endeared herself to him during the three-month term. Before she left, she gave him a very delicate, fine-tipped forceps that was perfect for gently grasping the tiny flaps in his cleft patients. From then on, whenever he used them, he would ask for his “Mary Lyns.” I told Lu this years later, after Dr. Millard had passed away. She never knew this little detail and I could tell she was incredibly moved to learn of this.

His sometimes-abrasive manner notwithstanding, Dr. Millard’s reputation and his results were not to be denied, and those that knew of it came to him from all over the world for surgery. During my term we saw the grandson of the ruler of one of the OPEC nations. The entourage that accompanied this infant included foreign and American bodyguards, nursemaids, a personal physician, servants, members of the immediate and extended family, and a representative from the U.S. State Department. During the child’s office visits, there would be several black limousines parked outside. I did the preliminary preoperative assessment and paperwork, assisted at surgery, performed all the postoperative care, and removed the sutures before the baby went home. It was a clear testimony to Dr. Millard’s trust in his residents, and his disregard for status, that he did not alter in any way his usual minimal involvement in the perioperative care for this VIP patient. For my part in caring for the child I received the gift of a gold Omega watch from the royal family, and everyone involved in the baby’s care received a very nice gift as well. Dr. Millard and his family were later flown to the country as guests of the royal family where he and his wife were feted and presented with solid gold Rolex watches. He wore his to our Monday breakfast the first Monday after his return and seemed, in equal measure, proud of the acknowledgement of his unique skills and somewhat embarrassed by the gaudy gift. I could not remember ever seeing him wear a watch before that. I never saw him wear it again.

In plastic surgery, precise planning and execution carry over to all facets of the procedure from the first cut, to the final stitch, and, in Dr. Millard’s program, even to the quality of the dressing placed over the surgical site. This compulsion to perfection in all aspects of plastic surgery finally led to a showdown with my boss.

It was customary for Dr. Millard to push the residents a bit to test their mettle. I think that he also wanted to see how we responded under stress. In one of those moments when he seemed to drop his guard, he once admitted to me that he never pushed his residents any harder than he himself was pushed by Gillies. The moment of truth came about midway through my time with him. We were on morning rounds, seeing the patients who had undergone surgery the previous day. One of these was a young lady on whom Dr. Millard had performed a rhinoplasty. Nasal surgery can be rather bloody so once the surgery is done, it is common practice to put a folded gauze beneath the nose and tape it in place to catch any blood which may dribble down during the first day or two.

At the patient’s bedside I removed the drip pad. When Dr. Millard had finished his inspection, I proceeded to put a fresh one on. I opened a package of gauze, folded the gauze pad in half, pulled some paper tape from a roll, tore off a piece, and bent down to secure the pad under the nose, just as I had done countless times in the past. This day, however, was different. No sooner had I torn the tape from the roll than Dr. Millard stopped me and said, “Do it like a plastic surgeon, not a goddamed general surgeon!” Though taken by surprise, I knew immediately what he was referring to. I redid the dressing, this time making sure both ends of the tape were cut cleanly square with a pair of bandage scissors, not torn raggedly from the roll. As we walked to the operating room I was subjected to a non-stop harangue regarding my flaws as a resident. “You just aren’t getting it,” he said and went on to say that he despaired of ever getting me to think like a plastic surgeon. He concluded by saying, “I don’t know why I ever accepted you into my program.” By that time, I was so shaken and angry that I did not trust myself to speak.

As we scrubbed side by side at the sink for the day’s first case, he continued in a more conciliatory tone, “You know, I had a resident once like you. He would never respond or react when I criticized him. Why don’t you say something?”

“Dr. Millard,” I began, “I don’t speak up because I don’t trust myself not to say something that I might regret when I am emotionally upset and angry. I believe that I am a good resident, and I don’t deserve the criticism that you directed at me just now.”

Nothing more was said but this incident was clearly a watershed moment that changed our relationship. Thereafter, it was noticeably less strained and confrontational. It became gradually clearer to me that Dr. Millard was trying to teach me, and the other residents, to think like plastic surgeons at all times. I believe that after that incident he finally felt he knew how far I could be pushed, and he no longer seemed to go out of his way to put so much pressure on me. There were times in the months that followed in which he opened up a little and shared some of his experiences from his own training. This was not to say that there were not other moments when he turned the screws a bit, but they were less frequent and more tolerable. His methods were unorthodox, and I can’t say I always understood or agreed with them, but they were, in the main, effective. Those of us who assimilated his lessons left the training program thinking like plastic surgeons. To this day I frequently recall, and try to apply, those lessons in nearly every case I do, and I always make sure my dressings are carefully placed, and I darn well cut the paper tape square with scissors, every time!

The above example of thinking like a plastic surgeon may seem extreme, and Dr. Millard’s biting critique uncalled for, but the importance of learning to think like a plastic surgeon cannot be overemphasized. Otherwise, we would have become nothing more than sophisticated “hole-fillers,” a term Dr. Millard sometimes used with disdain. I have observed plastic surgeons who, though clearly technically competent, must have come out of programs where this aspect of training was either absent or not emphasized. It shows in the quality of their work. From the planning to the execution there is an absence of the artistry that was a signature of Dr. Millard’s work and, hopefully, of those he trained.

Dr. Millard encouraged us to identify principles that spoke to our strengths and weaknesses. One of the principles enumerated in his book was make a plan, a pattern, and a second plan (lifeboat). As mentioned earlier, proper planning is crucial in plastic surgery and the more complex the problem, the more crucial good planning becomes. Another was perfect your craftsmanship. I was admittedly weak in the planning aspect, particularly in sorting through the possibilities for dealing with a complex reconstruction, but I tried to be meticulous in my execution. During one case presentation Dr. Millard pointed out some of the deficiencies in my planning, but did compliment me on the craftsmanship that I had brought to bear in performing the surgery and obtaining an acceptable result. It was a rare moment of affirmation.

Dr. Millard presented each graduate from his program with a leather-bound volume of Principlization of Plastic Surgery, embossed with their initials. In the flyleaf of mine he wrote, “To Rick. If you understand these principles and cling to them tenaciously- the mist will lift and eventually you should begin to make good plans (italics mine). D. Ralph Millard, Jr. 1989.”

In 2001, I saw a patient who had lost the columella of his nose from an infection. This is the bridge of skin and tissue between the nostrils from the top of the upper lip to the tip of the nose. Cody was a handsome three-year-old boy with a terribly snubbed nose. His story was a sad one of physical neglect and foster care after being taken from his parents by the state. He needed soft tissue to allow the nose to project properly. I wrote to Dr. Millard and sent him photographs of Cody to seek his advice on how best to correct this. He responded with a couple of suggestions. I considered those, then countered with an alternative that came to me after further reflection on the case and application of his principles. He liked it. His follow-up note to me read, “Excellent!! Whisker flaps are perfect if the upper lip is long. I never like to guess at problem solving cases when I do not have the patient in front of me. I did enjoy your solution.” I have kept his note as a treasured validation of my training right next to his flyleaf inscription in my book ever since!

The highlight of my two years in plastic surgery residency came, unsurprisingly, while working with Dr. Millard. Toward the end of my time with him, he was operating in the minor surgical suite in his office. I was assisting, and his nurse, Ellen, circulating. This was unusual in that we did not do much surgery in the office. The patient was the daughter of a prominent government official in South America. Gina was a wealthy, young socialite with an affinity for cocaine. The bridge of her nose had collapsed from long-term abuse. Cocaine causes a severe, extended constriction of the blood flow to the nose and this often results in necrosis of the supporting cartilage in the septum of the nose, which in turn causes the bridge of the nose to cave in as though squashed by a blow to the face. Dr. Millard was trying to figure out how to support a skin graft we had placed inside the nose to provide lining to the raw tissues in preparation for a later cartilage graft. I suggested trying some of the material used to obtain dental impressions on our cleft palate patients. We could mix it as a thick paste and insert it into the nose where it would solidify, making a solid, but soft, perfectly shaped custom insert which would securely support the graft. Dr. Millard liked the idea, and I left the room to get some of this material. Later, Ellen told me, in confidence, that while I was out of the room, he had said to her, “Rick is a pretty good resident, isn’t he?” It was the most effusive compliment I received during my entire residency and, true to form, he never told me this to my face. I don’t think that Dr. Millard ever appreciated what this meant to me. For the rest of the day, I was on cloud nine.

Watching Dr. Millard operate, especially when performing repair of a cleft lip or palate, was to experience a rare privilege. Despite his large hands, his surgical touch was about the most gentle of any surgeon I have worked with. His delicacy in working with itty bitty flaps of tissue on tiny infants was nothing short of uncanny. You had the feeling that he could do things with tissues that would have defeated a lesser surgeon. He had an ability to visualize complex three-dimensional flaps and move them into their desired positions that I could only observe with envy. At the time I was there, he was working on a new technique for inducing bone formation across the gap in the alveolus, the bony ridge of the upper jaw from which teeth erupt. In the past, it was necessary to use bone grafts in this space to bridge the gap and support eruption of the permanent teeth. Children with cleft palates that include the alveolus always have problems with this and require extensive orthodontic work. In Dr. Millard’s procedure, tiny flaps were designed and cut, then moved across the gap to create a tube of tissue that would produce bone naturally, avoiding the need for bone graft surgery later and facilitating normal tooth eruption. The procedure was demanding and required working in a tight space with tiny flaps that were exceedingly fragile. Few surgeons who would have attempted this, and fewer still could have done this successfully. Even today, there are few surgeons who do this.

As the end of my rotation approached, the relief at surviving those four months was tinged with genuine regret at the completion of this once in a lifetime experience of working with a surgeon who was truly one-of-a-kind. It is not often we get to work with an icon in any professional field. I have been grateful for the opportunity ever since.

Richard T. Bosshardt, MD, FACS, Senior Fellow at Do No Harm, Founding Fellow at FAIR in Medicine

My book is also available on Amazon as an eBook or in paperback.

Good teachers are priceless.