The Making of a Plastic Surgeon- Two Years in the Crucible Learning the Art and Science

Chapter 7- Hand surgery and return to Jackson

“Don’t rule out working with your hands. It does not preclude using your head.”

Andy Rooney

At Oaknoll Naval Hospital, hand surgery was the province of the Department of Orthopedics and the sole hand surgeon was Charlotte Alexander, a tiny wisp of a girl who had just completed her hand surgery fellowship. She was the antithesis of the stereotypical orthopedic surgeon- a male who would look at home in an NFL locker room. Charlotte was so petite that we semi-seriously wondered if she shopped for her clothes in the children’s department. Although I rotated on the orthopedic service, I had few opportunities to work with Charlotte, so I had relatively little exposure to hand surgery before coming back to Miami.

The subspecialty of hand surgery covers the hand to the elbow. Its practitioners can come from several specialties, including orthopedic surgery, general surgery, and plastic surgery. Dedicated hand surgeons complete a full residency in one of those specialties, then undertake a year-long fellowship dedicated solely to hand surgery, after which they can obtain a Certificate of Added Qualification in Hand Surgery from the American Board of Medical Specialties. The complex anatomy, unique functional capabilities, and critical importance of our hands make this a challenging and fascinating field.

At Jackson, hand surgery was a division within the Department of Orthopedics, just as plastic surgery was a division in the Department of Surgery. It was the only rotation in the residency in which we officially, and with Dr. Millard’s blessing, came under the tutelage of doctors who were not plastic surgeons. The Chief of the Division of Hand Surgery was Dr. William Burkhalter. Dr. Burkhalter was one of the top hand surgeons in the country. He had authored countless papers and book chapters and was a force to be reckoned with. He was a superb teacher and I looked forward to any opportunity to work with him. Burkhalter was as demanding of his residents as Dr. Millard, but friendlier and more approachable. He retired from the Army Medical Corps with the rank of colonel before coming to Miami in 1974 to head the Division. Despite his civilian status, he was frequently addressed by his military rank. He looked very fit and retained his military bearing right down to the ramrod-straight posture and close-cropped hair. The other attendings in the Division were Drs. Ron Carneiro and Kathleen Oulette. Carneiro was a plastic surgeon from Brazil. Because of my Brazilian heritage, we hit it off immediately. Oulette was an orthopedic-trained hand surgeon. Both Carneiro and Oulette were very pleasant and easy to work with.

Burkhalter ran his service with a degree of efficiency without which things could have easily descended into chaos just from the sheer volume of hand surgery, which was staggering. Compared to the relative quiet of the plastic surgery division, arriving on the hand service was not unlike jumping on an unbroken bronco where you just hung on for a wild ride. Each morning, all members of the hand surgery team gathered to make rounds on patients in the hospital. With the census sometimes thirty or more, and patients scattered wherever there were available beds, this could take hours. As rounds progressed, the dozen or more participants were whittled down as residents and attendings would peel off to go to surgery or clinic and rounds would usually finish with two or three team members.

Burkhalter’s bedside manner was, to say the least, unconventional. His was a no-nonsense approach which only thinly veiled a real concern for the patients. He radiated an air of authority which compelled patients to comply with whatever he told them to do. In hand surgery, the aftercare is as important as the surgery, sometimes more so. Many complex cases, such as tendon repairs and reconstruction, and severe soft tissue trauma, require lengthy hand therapy in order to obtain the best possible functional result. Patient compliance with therapy is crucial since a non-compliant patient can undo the work of even the very best surgeon. When Burkhalter learned that a patient was not complying with their hand therapy he would become livid. He would stand there, rigid, his face beet red, the very picture of indignation that any patient could be so derelict as to not cooperate with their care. He would deliver a tongue lashing that would leave the patient, and everyone within earshot, ready, indeed frantic, to do his bidding. I was never sure if this was real, or a deliberate attempt to grab the patient’s attention. If it was an act, it was worthy of an Oscar. Either way, it usually worked!

At the end of each working day, the resident and hand fellow on call that night for the hand service were charged with operating on the backlog of urgent and emergency cases awaiting surgery. There were patients with severed tendons and/or nerves, fractures, hand infections to be drained, soft tissue injuries to be debrided and sutured, and amputations to be done. As soon as an operating room became available, the fellow and I would swing into action and operate until we ran out of patients or a case of greater priority from another service bumped us on the schedule. Sometimes, we operated through the night. When two rooms were available, we would split cases. It was always a point of pride to report at morning rounds that we had cleared the surgical schedule of all backlogged cases. Of course, like a surgical version of story of Sisyphus, by the end of the day there would invariably be another backlog to deal with.

The Division of Hand Surgery offered two fellowship positions. When I was there, one fellow was an orthopedic surgeon and the other was a plastic surgeon. They were very good in sharing cases with the residents, reserving only the most complex cases for themselves. In those two months, I repaired tendons, nerves, and blood vessels, performed various types of amputations, removed benign and cancerous tumors, released trigger fingers, corrected contractures of the fingers, reduced and plated fractures, fused joints, and did a variety of flaps for reconstruction of the hand. I also assisted in a wide variety of more complex hand surgeries, such as joint replacements and even a couple of microsurgical cases including transfer of a big toe to the hand to create a new thumb. Carneiro and Oulette were both interested in microsurgery and were the first to perform this type of surgery at Jackson.

The Division of Hand Surgery was responsible for running a microsurgery laboratory which was housed in the medical school building across from Jackson. Orthopedic and plastic surgery residents rotating on hand were sent over there for a two-week course in microsurgery. We would spend each day operating on rats, cutting and then repairing tiny arteries and veins to learn and hone the fine motor skills necessary for this until we became consistently successful. The lab was also a place to practice before an upcoming micro case. I enjoyed microsurgery and hoped to incorporate it into my future practice.

Unlike the Division of Plastic Surgery, the hand service functioned as a cohesive team, I think this was, in large part, due to the fragmented nature of our service, with our residents scattered beyond Jackson, and to the absence of a true Jackson plastic surgery team. The plastic surgery residents were made welcome on the hand service and treated the same as the orthopedic residents and fellows. I like to think that we pulled our weight. We were even included in informal and formal social gatherings. It was common for team members to meet at local watering holes after hours. Over the Christmas holiday that year, the entire hand service was invited to Burkhalter’s home for dinner. His wife made a huge vat of jambalaya. For Sally and me, it was one of the most enjoyable evenings of those two years and remains one of my fondest memories of my residency. Burkhalter always looked the picture of health and I was shocked and saddened to hear that he passed away unexpectedly three years after I left Miami. The two-month rotation on the hand surgery service carried me through the end of 1987.

On January 1, 1988 I returned to the Jackson service for my second two months as a junior resident. My senior resident for this period was Ed Bednar. Like Raiffe, he was generous and unselfish in handing over cases to me. He was an excellent surgeon and I learned a great deal from him. Even in the mix of backgrounds of the residents, he had an unusual pedigree for a plastic surgery resident, which clearly piqued Dr. Millard’s interest. Bednar had an extensive artistic background and had been trained how to carve wooden duck decoys by one of the best professional carvers. Ed had numerous awards of his own to his credit in this area. He once showed me one of the few decoys that he had kept for himself. It was phenomenal. The decoy was carved down to the finest details of the feathers and appeared as lifelike as a real duck that had been prepared by a good taxidermist.

I picked up right where I had left off with Bednar. By now, however, I was doing more cases as the principal surgeon, with him assisting me rather than vice versa. These included most of the jaw fractures that we took to the operating room. I was more comfortable with these now and did not stick myself so often with the sharp wires. Because I was now becoming more independent, Bednar and I would often operate separately, one of us in the main operating room and the other in the cosmetic operating room one floor up.

Every teaching hospital has patients whose purpose in life seems to be to train doctors. They have complex, and usually chronic, medical conditions and are treated by multiple generations of residents. Maurice was one of ours. When I met Maurice in the resident’s clinic at Jackson one morning, he was still a work in progress. Bednar greeted him like an old friend as we entered the exam room.

“Hey, Maurice,” Bednar said to the gentleman standing there. “How ya doin’?”

“Great, Doc, I didn’t need no pain meds this time,” was the cheery answer.

“Good, good. Let’s see how things are coming along“, said Bednar, as he removed the dressing on the left side of Maurice’s face and leaned in for a closer look.

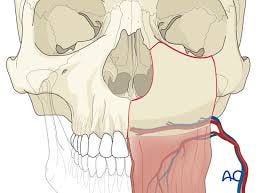

I leaned in as well and……just stared. Maurice was Haitian, a soft-spoken, middle-aged black man of average height, with graying hair and a scruffy beard, at least on the right side of his face. The left side of his face was, well, mostly missing. Maurice had once suffered from depression and, in a moment of unusually severe despondency years earlier, he had tried to relieve his depression with a 12-gauge shotgun. The ensuing blast took out his left lower jaw, cheek bone, and much of the left eye socket, including his left eye. Incredibly, the injury was not fatal and Maurice survived, only to be left with a grotesque hole where the left side of his face should have been.

Ironically, the blast not only took away most of the left side of his face, it also cured his depression and gave him a reason to live. The unexpected outcome of this terrible injury was that he acquired a new purpose in life, one that he pursued with a remarkable degree of good-natured enthusiasm: training several generations of plastic surgeons. He always seemed to be in good spirits and accepted without apparent rancor the unusual direction his life had taken.

The residents who had just preceded us had done some skin grafting to his reconstructed eye socket to prepare it for fitting for a glass eye. He had already undergone numerous procedures including tissue expansion and a variety of grafts and flaps to get to this point. He was a walking, talking collage of reconstructive facial surgery. At this time, he was still missing the bone in his cheek and upper jaw. The absence of a bony foundation caused the soft tissues to cave into the large hollow left behind. Maurice was doing well this go around but would provide surgical opportunities for many future residents. I was to take part in the next chapter of his reconstructive saga later.

This period at Jackson coincided with the annual Baker and Gordon Symposium held each February. Drs. Baker and Gordon hosted one of the most popular annual symposiums in cosmetic plastic surgery in the U.S. The symposium celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2016. The location in Miami, the subject matter, and the reputation of the hosts, ensured that it was always well-attended, and the list of guest lecturers and attendees included many of the best known plastic surgeons from the U.S. and around the world. The event always kicked off with an evening meet-and-greet cocktail reception at their office followed by two days of lectures and panel discussions in one of the downtown Miami hotels. The residents at the program in Miami had a standing invitation to attend the symposium and the substantial registration fee was waived for us. The three senior residents always attended, while the three junior guys covered for them and attended only as their workload allowed. One of the highlights of the weekend was that we were treated to dinner at a fine restaurant, with our wives, by one of the companies that exhibited their wares at the symposium. In today’s world, this would have been disallowed as some sort of influence to get us to use the company’s products, but for us residents it was a rare chance to have a very nice evening out with our wives at no expense. I doubt that any of us felt any obligation as a result and, besides, we had no say in the purchasing decisions of the Division in any event.

The signature feature of the symposium was live surgery performed by invited plastic surgeons. Baker and Gordon pioneered live surgery by leaders in the field of plastic surgery at this meeting. Some were recognized for their expertise in a particular area. Others had a new procedure or their own modification of an existing operation to demonstrate. The surgery would be done at nearby Mercy Hospital and televised live to the audience in the hotel auditorium. There was a two-way hookup allowing attendees in the auditorium and the surgeon in the operating room to communicate back and forth during the surgery. Patients were chosen in advance by Baker and Gordon or, in some cases, the surgeon brought a patient of their own with them to Miami. The live surgery demonstrations were a chance for us to see some of the best surgeons in the world at work and were hugely popular. Some of cases were unforgettable.

One plastic surgeon had devised his variant on the traditional facelift. Instead of lifting the skin, then tightening the skin and muscle layers separately, he elevated the tissues in a deeper plane, under the muscle, right down onto the bone, lifting all the layers together rather than separately. This technique, he claimed, produced longer lasting, more natural results, with less risk of bleeding after surgery. One of the truly feared complications of facelifts is bleeding under the skin flaps, which may require emergency reoperation and mar the outcome. He assured the audience that he had never had any patient bleed postoperatively after his procedure. Of course, you guessed it, his patient bled that night and had to be emergently returned to surgery. What he failed to share was the prolonged healing and many months of swelling patients experienced after this technique. You don’t hear much about this technique today. I don’t think this presentation helped the cause.

Another case was truly bizarre. This surgeon was known for his use of cartilage grafts in cosmetic rhinoplasties (nose jobs). Plastic surgeons were moving away from the classic overdone rhinoplasty that aggressively removed cartilage and produced an entire generation of patients with identical, small, bobbed noses that did not always match their face or ethnic background. The goal shifted to producing a more subtle, nuanced look that was more suited to each patient’s unique face and true to their ethnicity. In these, newer rhinoplasties it was common to harvest some cartilage, usually from the nasal septum, the wall that divides the two halves of the inner nose. This could be used as a graft to enhance the shape of the nose.

This surgeon began by slickly harvesting an impressive piece of cartilage from the septum. There were murmurs of approval and admiration from the audience. He then cut up the graft into small pieces and, to the astonishment of all, proceeded to insert every single piece back into the nose, cramming them seemingly anywhere he could. I don’t know if he just got carried away or felt it was a waste not to use all the material he had harvested. With each added piece of cartilage, the nose grew larger, like a surgical version of Pinocchio. The din in the auditorium increased as the audience watched with growing consternation and, finally, alarm as the nose got bigger and bigger. By the end of the case, the auditorium was buzzing as incredulous attendees turned to one another and asked, “Do you see that?” The other residents and I just sat there, staring at the screen in disbelief.

A couple of surgeons in the audience politely voiced concerns to the surgeon in the operating room but these were dismissed because the shape of the nose looked good. The fact that it was better suited to someone with a head twice as big seemed to be of no concern. The surgeon apparently felt that nothing was amiss and was clearly pleased with the outcome. The patient, a young man desiring a more refined nose, began with a large, hooked beak of a nose. When the operation was completed, his nose had a nicer shape, to be sure, but was much larger than what he started with. We later learned that he was inconsolable postoperatively. A short time after the symposium, one of the doctors in the Miami practice took him back to surgery, removed nearly all the grafted cartilage, and obtained a satisfactory result for him.

There was a theatricality to some of the surgical demonstrations that seemed a little over-the-top. One surgeon from Texas demonstrated his technique for breast augmentation that he claimed was atraumatic and painless to patients. To underscore this, he gave his young patient a video camera so that she could document her visit to the local discos and nightspots in Miami Beach the evening of her surgery, dancing the night away. She certainly seemed mobile and looked unimpaired; long- acting local anesthetics can do that, but I could not help but wonder how she felt the next day. I never did find out. Despite the success of this presentation, I have not seen any trend in the decades since to encourage postoperative breast-augmentation patients to go out and paint the town right after surgery.

Live surgical demonstrations, while a helpful teaching tool, were also a double-edged sword for the operating surgeon. There were only four possible outcomes of which three were potentially detrimental to one’s reputation. In the best-case scenario, the surgery could be successful and well received by attendees. It could be well received yet go poorly as with the deep plane facelift. It could go well but be poorly received as happened with the first tissue expansion. Plastic surgeons are very quick to criticize their peers, especially in cosmetic surgery, which is very competitive. In the worst case, it could be poorly received and turn out badly as with the young man and his rhinoplasty. I quickly resolved that, if I were ever invited to perform a live surgical demonstration, I would politely, but firmly, decline.

On completion of my second term at Jackson, I returned to Victoria for my last two months there.

Victoria wasn’t really a teaching hospital. The only trainees there were the plastic surgery residents from the Jackson program and Wolfe’s craniofacial fellow. Even so, Tony occasionally brought a patient there for surgery that was covered by Florida’s Children’s Medical Service program for indigent children or even brought patients with facial deformities from overseas, usually South America. Even though Victoria was a private hospital, the administration would provide the hospital’s resources for the occasional charity patient. It was a win/win that was good for the patient and good public relations for the hospital to have someone as illustrious as Tony performing surgery there. I now had a better grasp of craniofacial surgery, but I could not imagine tackling these complex cases without additional fellowship training after my residency as some residents did when they went out to practice. Some of the younger residents seemed to be fearless in taking on cases that would have given experienced surgeons pause.

During this period Wolfe performed a case that combined his craniofacial skills with microsurgery. Alicia was a young girl from South America. She had suffered a severe infection of her face that ate away much of the soft tissues of the cheek and some of the cheek bone. Her deformity was similar to, but not as severe as, that of Maurice. Wolfe invited Joseph Banis, a well-known microsurgeon and friend from the University of Louisville, to assist him. Banis brought his own fellow along to participate in Alicia’s reconstruction. The plan was to harvest tissue from Alicia’s hip to put into her face. This graft would include a portion of the iliac crest- the hip bone- to replace the missing bone of the upper jaw, and a paddle of skin and fat to replace the missing fat and skin in the cheek. All of these would be supplied by a single artery and a pair of veins. They would have to be connected to a recipient artery and two veins in the face. Most small to medium-size arteries are accompanied by two veins and it is best for both to be hooked up as this provides a backup in case one vein clots. Every aspect of the surgery was critical to success. The facial defect had to be carefully dissected out, especially the blood vessels. The graft had to be harvested in perfect condition. There was no margin of error in the microsurgical connection of the tiny blood vessels. If either the artery or the veins did not provide adequate blood flow, the flap would die.

Wolfe and Banis did a dry run the day before surgery to fine tune everything, from the instrumentation, to the position of the patient in the room, to the location of the operating microscope so two teams could work simultaneously. Nothing was left to chance. The surgery took most of the next day. Wolfe and his fellow harvested the graft, then opened the cheek to re-create the original defect on the face. Meanwhile Banis and his fellow dissected out the blood vessels at the hip and in the face. The bone was taken in such a way that, once the graft was removed from the surgical field, the remaining bone of the hip could be repaired, leaving no noticeable defect beyond the scar on the skin. Throughout the operation, the two teams compared notes frequently to be sure the bone graft was of the right size and shape, the skin taken was sufficient to replace the missing skin of the cheek, and that the blood vessels would be able to be connected without tension. By the end of the day, the surgery was finished. Everything went perfectly. On rounds the next morning, the team’s efforts were rewarded by a robust, clearly viable flap and a patient who, despite her discomfort, had a happy, if slightly crooked smile. This was easily one of the most complex surgeries I had ever been involved in, even if only as one of the substitute assistants during the procedure. That this level of work was in the domain of plastic surgery was both sobering and very exciting.

May 1988 rolled around almost before I knew it and it was time to rotate onto Dr. Millard’s service.

Richard T. Bosshardt, MD, FACS, Senior Fellow at Do No Harm, Founding Fellow at FAIR in Medicine

If you would like to read ahead or just obtain your own copy for yourself or as a gift, you can order from Amazon in eBook or paperback.